Published by Reuters in March 1992

As the sun’s first rays stretch across the sands of Bondi Beach and onto its ageing 1920s shops, Australia’s most famous beach looks a little seedy and hung-over.

Saturday night is party night at Bondi. Sunday morning is not a pretty sight. Garbage bins overflow with refuse from late-night take-away diners: pizza cartons, hamburger wrappers and cans of Foster’s beer litter Campbell Parade which skirts the beach.

Mini-skirted party girls wearing enough make-up to plaster the crumbling Hotel Bondi scurry home.

Agile joggers in swimsuits sidestep a few bleary-eyed tourists with British accents who wobble drunkenly head-first into the surf, jeans and all.

Before long, it’s the turn of the elderly migrants from eastern Europe, power-walking along the concrete promenade in a uniform of tracksuit, towelling headband, sandshoes and thick gold jewellery.

In the water, bobbing up and down like circus seals in fluorescent costumes, are Bondi’s famed surfers.

Scores of young Japanese, in Australia to learn English, join the line-up in the water as long as the waves stay waist-high. When the swells grow, their numbers thin.

Despite its jaded appearance Bondi has become home to a potpourri of nationalities.

The Waverley municipality which surrounds Bondi, covering nine sq km (three sq miles), is home to more than 60,000 people. According to the latest census 39 per cent were born overseas, 24 per cent in non-English speaking countries.

Walk along Campbell Parade and you will hear not only various versions of English, but more than 25 other languages, mostly east European, Russian, Hebrew, and Spanish.

By mid-morning the screams of young children echo from the northern end of the beach as Australia’s junior surf lifesavers, the Nippers, go through their paces.

North Bondi is the domain of the beach’s long-term, working class residents. The small ocean rock pools offer safe swimming for children, while Ben Buckler, Bondi’s northern point, shelters mothers and babies from summer’s blustery nor’easterlies.

Overlooking the northern corner is Tobruk House, a club for returned servicemen, an enclave of conservative Australia circa 1940s — cheap beer, bingo and weekly in-house movies.

In stark contrast, the southern end of the beach is Australia 1992; hedonistic, trendy, loud and naked.

On two cylindrical ramps heavily-padded skateboarders perform their landbased surfing before wide-eyed tourists.

Renovated blocks of flats have been turned into chic cafes where a capuccino sipped over the morning papers is de rigueur for writers, artisans and actors — Bondi’s newest arrivals.

By midday, when the blistering sun is high above, the southern sands are littered with naked and semi-naked bodies, their owners oblivious to the fact that Australia has the highest skin cancer rate in the world.

One woman sunbather has two swimming costumes — one to wear on the beach, the other in the water. For some men a small pouch and a piece of string suffices.

Bare flesh attracts not only sand flies but voyeurs who linger nonchalantly on the promenade. But no one seems to mind — after all, this is the beach where the local boardriders’ club is called ITN (In The Nude).

Carved out of the rocks that form the southern point is the white-washed Bondi Icebergs swimming club, established in 1929. Just 1.15 dollars (1.12 U.S.) buys a glass of beer and the best view of Bondi, albeit it through salt-encrusted windows.

On the first day of winter each year the elite male club, the Icebergs, throw huge chunks of ice into their ocean pool before diving in.

As Bondi bakes, the air fills with exotic smells from Thai, Vietnamese, African, Italian, and Lebanese restaurants.

Bronzed inspectors cruise up and down the beach, walkie-talkies in hand. In the first two months of 1991, around 500 people, many of them Japanese or English, had to be rescued from Bondi’s pounding waves, despite multi-lingual signs stating where swimming is safest.

By mid-afternoon, a cacophony wafts through the heat from the Bondi Pavilion, where a reggae band seduces dreadlock dancers and first generation Italian-Australians strut to ghetto-blasters.

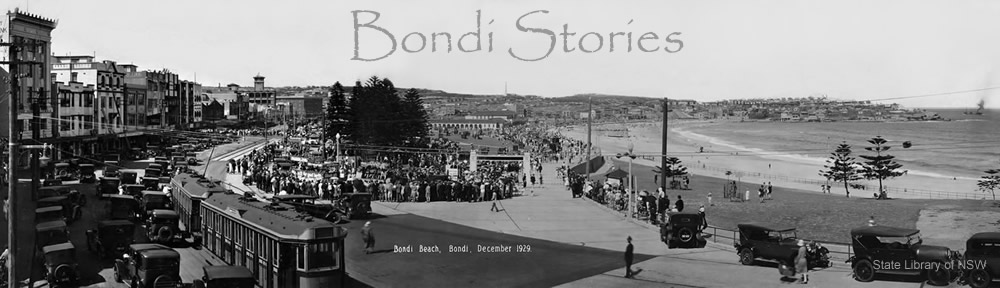

In the 1930s, when a crowd of 80,000 sun worshippers was not uncommon on a hot weekend, the pavilion was an open air venue for tuxedoed big bands.

Today it is a community centre featuring yoga and aerobic classes, as well as a money change and souvenir shop for busloads of Japanese tourists.

As dusk descends the east European migrants return with their families for an evening stroll along the promenade before dinner at either the Jewish Hakoah Club or the Russian Black Sea restaurant.

Anglo-Saxon Australians have deserted the beach for dinner in front of the television and the Sunday night football replay.

By nightfall, the beach is empty but for the surfers who stay long after dark waiting for that one great ride.

MICHAEL PERRY

Don’t get too excited about new “melting pots”. The old one works just fine and you don’t have to look far from Bondi to see what is happening in other “melting pots” in Sydney. You know the old saying “you don’t know what you’ve got till its gone”.

The potential problem with cultural melting pots is that the original, host cultures in time may be entirely melted away.